By Guillermo Velasco

Associate Professor of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology I, University Complutense of Madrid and member of the board of directors of Observatorio Español de Cannabis Medicinal.

Research undertaken over the past few decades has helped us develop a thorough understanding of the cellular and molecular bases on which cannabinoids act within our organism. We therefore know quite a lot about the therapeutic properties of some cannabinoids (principally delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and, to a lesser degree, cannabidiol (CBD)), which means that we also know much about the preparations or extracts derived from cannabis that contain different proportions of them. However, despite this progress, many questions still remain unanswered. This makes it essential for many more studies to be carried out, both basic/preclinical and clinical, since this would make it possible to sometimes consolidate and, at other times, to explore or corroborate the usefulness of cannabinoids and their products in the treatment of different illnesses.

In this paper, I first review the steps that are usually taken to develop new drugs, and then I share my thoughts on how the development of clinical studies with cannabinoids could progress in a joint effort. I believe that this type of research could be an efficient way to develop and incorporate natural cannabinoids as another therapeutic tool used to manage different disorders.

The process to develop and approve a drug

A highly significant number of the medicinal products that are available today followed a long developmental process that culminated in approval by regulatory agencies. It must be stressed that this process is largely based on the work of the pharmaceutical industry. This is why, before referring to the situation of cannabinoids, I briefly summarise the elements of this process and then analyse, in a suitable context, the predicament faced by the sector holding cannabinoid medications, especially that of natural cannabinoids and medicinal cannabis.

The development of a new drug usually starts with the identification of a molecule or molecules with potential therapeutic activity. This identification is often achieved through a screening process, which makes it possible to find those with greater biological activity that could potentially lead to the development of a new drug. An essential issue on which the pharmaceutical industry is based is the protection of this new molecule or molecules. They are patented as soon as they are identified as compounds that are potentially useful. This process ensures that the molecule in question belongs to whoever patented it. This preserves the exclusivity of its use during a certain period of time. We will return to this topic later, since it is fundamental to understanding how the system works and the position of several cannabinoids.

In any case, once it has been identified, a candidate molecule must follow a long process of analysis in different cellular or animal models to discover whether its biological activity is sufficiently promising. In a similar, no less important, manner, one must analyse whether the physical-chemical properties of the molecule give it sufficient stability and also allow it to potentially be incorporated into pharmaceutical preparations, which can be administered to patients through a suitable route. It must also be viable in patients presenting with a certain pathology. Furthermore, tests must be made in animal models in order to ascertain how this molecule is metabolised. These assays are necessary to ensure that the molecule can reach effective therapeutic levels in the organism. One must also check that the administered compound does not produce toxicity, or that when the organism metabolises this compound, it does not produce a toxic by-product of the molecule. It is, therefore, a process that usually takes several years and during which most candidate molecules are rejected for one reason or another.

Compounds that make it beyond these initial phases and that are considered promising, stable and non-toxic—at least in animal models—can be selected to perform clinical trials. The clinical trial phase is the most expensive period in the process. Clinical trials start with an initial phase (phase I) to evaluate in a few patients any possible toxicity in humans of the compound or molecule being tested. Then, if phase I is ended successfully, the compound goes on to phase II, which focuses on obtaining the first indices of therapeutic efficacy of the molecule in humans. For this purpose, the effects of treatment with the study drug are usually compared to those of a placebo (a compound with no therapeutic activity) or—depending on the disorder—with another treatment that has already been approved and is normally used to treat patients with this disorder. The cost of this second phase in the clinical study, which usually involves dozens of patients, tends to average around several hundred thousand euros. If promising results are still obtained in this second phase, suggesting that the drug may be effective to treat the disorder, then the road is cleared to continue to phase III. This phase includes the analysis of the efficacy of the compound in hundreds, sometimes thousands, of patients in different hospitals and, often, different countries, in order to reach almost-definite conclusions regarding the efficacy of the drug. The cost of this phase is usually of several, frequently a couple dozen, million euros, which is why it can usually only be covered by companies with a high investment capacity or by the public sector. A successful phase III study, whose detailed statistical analysis can conclude whether treatment with the drug is effective and safe (in many cases, it is also required for it to be more effective than other drugs already being used to treat the disorder), would lead to the approval of the use of the drug by state or multinational regulatory agencies (e.g. AEMPS (Spain), EMA (Europe), as well as the FDA (Food and Drug Administration, USA)). This approval would imply its inclusion on the list of drugs approved for use in the treatment of the particular disorder for which the study was conducted. The last phase (IV) corresponds to surveillance, which entails the analysis of the efficacy and safety of the drug once it is prescribed and administered to patients in a more widespread manner.

In the current system, the benefits of marketing a drug lie in the exclusivity of its distribution thanks to the patent system

At this point, patients can now benefit from the new drug overall, but the pharmaceutical company—which invested a considerable amount of money to develop it—starts to reap the economic benefits from its sale and distribution. And here we return to the patent issue I mentioned before. Once this entire process has been completed, a certain company obtains a compound that managed to overcome all the obstacles, and is finally approved by regulatory agencies. The feature that makes the process profitable for the company is that only that company has the right to exclusively produce and distribute this drug for a defined number of years. This also lets the company negotiate a sales price with its clients. And, of course, the pharmaceutical companies' biggest client—at least in Europe where social security covers most of the cost of medicinal products—is the public sector. Several full articles could be written on the intricacies of this multimillion negotiation. However, suffice to say that the final balance after having exclusively exploited approved drugs amply compensates the investment that is made. Once patents expire and exclusivity is lost, other companies can manufacture the medicinal drug, which can then become a so-called "generic drug" with a lower sales price and profitability. Consequently, understanding how the pharmaceutical industry obtains enormous benefits each year, making it one of the most profitable (legal) businesses, is food for thought.

Let us now analyse, superficially at least, the situation of cannabinoid drugs, that of natural cannabinoids, and that of medicinal cannabis, as well as the approaches followed so far to develop them.

Situation of cannabinoid drugs

The use of marijuana and its derived products for therapeutic purposes by many patients, but above all in some pathologies related to the side effects caused by cancer chemotherapy and AIDS, as well as other illnesses such as multiple sclerosis, revealed great potential in the pharmacological exploitation of the endocannabinoid system. Also, as different elements in this system and its physiological functions were identified, it was demonstrated that the development of compounds that could modulate it was of great interest from a therapeutic standpoint.

Different conventional pharmaceutical companies have therefore tried to develop their own compounds that act on the endocannabinoid system. In general, three strategies have been used that follow the development model described above: (i) identification and development of cannabinoid receptor agonist molecules (i.e. compounds that activate these receptors); (ii) development of cannabinoid receptor antagonist molecules (i.e. compounds that block them); and (iii) development of compounds that block endocannabinoid degradation and, therefore, help increase their levels in the organism. These compounds also produce the activation of cannabinoid receptors, albeit indirectly.

For different reasons, until now none of these strategies have been very successful in the face of the development of new drugs. Several very powerful cannabinoid receptor agonists have been produced, but the potential side effects in humans related to elevated psychoactive effects have encumbered their development. Therefore, it does not seem that new drugs will be produced if this path is followed, at least not in the short term. As for cannabinoid receptor antagonists, the pharmaceutical company Sanofu developed Rimonabant, a CB1 receptor antagonist, which was developed as an anti-obesity drug called "Acomplia". The drug was approved, but was withdrawn from the market when it was observed that the inhibition of the CB1 receptor could cause depression in patients who were being treated with it. Finally, several companies are currently trying to develop inhibitors for some of the enzymes involved in endocannabinoid degradation. In 2016, a serious accident occurred during phase I of the clinical trial of one of these inhibitors (BIA 10-2474). The incident caused the death of one phase I volunteer and serious neurological symptoms in others. Although it is highly likely that this accident was due to an unspecific effect of the compound, it is true that the situation that ensued has done much to slow down the development of other drugs with a similar mechanism of action.

Ultimately, although we should not entirely discard the possibility that future drugs may appear based on any of these three or other strategies, such drugs are not expected to be available in the short or medium term.

Cannabinoid medicinal drugs based on natural compounds

Thus, the type of approach that has been developed most frequently to date is the therapeutic use of natural cannabinoids from the plant or other slightly modified ones derived from them, though it is also associated with a few complications that we shall now discuss. In fact, the active substance of the first cannabinoid drugs was THC or a synthetic form of it (dronabinol), which is the basis of the medicinal product Marinol. This drug was approved in the 1980s for several uses, including to control nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy, and later as an appetite stimulant for AIDS patients. A similar approach was achieved with nabilone (Cesamet), in this case with a molecule that was highly similar to THC but with a slight modification, which was also approved for similar uses. Neither of these two medicinal products is widely accepted, mostly due to their psychoactive effects, which limit the dosage range at which they can be used. Their application has, therefore, been rather restricted.

Here it is important to consider that, unlike the compounds discussed just above (all chosen for their capacity to act on a certain molecular target), natural compounds, such as THC or CBD, cannot be patented. However, the use of certain combinations of natural compounds or specific preparations of such combinations for certain uses can be patented.

Thus, substances from Cannabis sativa are also found among cannabis drugs. These extracts (or botanical drug substances) contain a mixture of cannabinoids whose composition is controlled, as well as other components from the plant, though the latter in much smaller amounts. The most important advantage of this approach, which we shall return to when we go over the medicinal cannabis option, is that the plant preparations not only contain THC but also CBD and other cannabinoids, which makes them much better tolerated by patients, who experience fewer psychoactive effects. Medications of this kind that have been approved are principally: Nabiximols (sold as Sativex and produced by GW Pharmaceuticals), which is a mixture of two different extracts from Cannabis sativa that contain equal amounts of THC and CBD, and Epidiolex, which has mostly CBD and very small amounts of THC (also produced by GW Pharmaceuticals). Many clinical trials have been conducted with these drugs, which have finally been approved for some applications in Europe and Canada (Sativex to treat the pain and spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis) and in the United States (Epidiolex to treat refractory epilepsy syndromes in children).

Situation of medicinal cannabis

Last but not least, we have the medicinal cannabis programmes that are also based on the use of cannabis drug substances or preparations and that are already being implemented in many countries. I will not go into detail in this article about these programmes because they have already been covered extensively by other papers published in this same forum. In any case, unlike the medications described above, the composition of these extracts is more variable because they may contain different proportions of cannabinoids, and it is frequent for the composition of different batches to vary from one to another. On the other hand—although in practical terms they could be considered equivalent to generic medications that contain the same active substances as the plant—their use in different applications in most cases is not substantiated by clinical trials specifically conducted to prove the efficacy of each substance in particular.

It is crucial that we conduct more clinical trials with cannabinoids

Many analyses, including a well-known one by the National Academy of Sciences in the United States, have studied the evidence obtained by clinical trials developed to test the efficacy of cannabinoids to treat different diseases. As discussed in this forum (e.g. the summary published by Ekaitz Agirregoitia), these analyses have enabled the conclusion that there is hard evidence of some of the therapeutic activities of cannabinoids, while for others the evidence is less solid, moderate, or inconclusive.

Why is the evidence moderate or inconclusive in some cases? One possibility might just be that cannabinoids were not effective to treat these disorders. But in most cases, the answer is simply that we do not have enough information from clinical trials to be able to reach a definite conclusion. Sometimes this is because very few clinical trials have been conducted for a certain application, and other times because the design of those that were finished is flawed. These problems may be varied; for example, they were not made with a number of patients large enough to reach a statistically significant conclusion, or a suitable control group was not included, or they definitely could not be compared to each other, and so on. In the face of this situation, and as commented at the beginning of this paper, it is crucial that we conduct more and better clinical trials to help bolster and consolidate the therapeutic application of cannabis and its derived products.

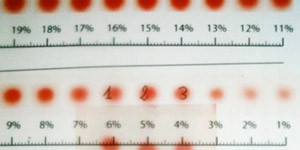

Based on what we know today, the cannabinoids that are responsible for most of the therapeutic activity of marijuana and its derived products are THC and CBD. Therefore, it must be a priority for such trials to be developed with drugs (this category must also include botanical drug substances or pharmaceutical-grade preparations) that contain well-defined amounts of these two cannabinoids. These trials will be fundamental to obtain harder evidence of some of the therapeutic properties of these two compounds, to better know the optimal dosages and the best administration routes for each type of illness, and also to understand the molecular characteristics that determine a good or bad response, or serious or mild side effects, after receiving treatment with these compounds.

How to go forward to develop more clinical trials with cannabinoids?

As discussed above, the process to conduct clinical trials is not easy. First, it is essential to have medications that meet the requirements demanded by the regulatory agencies regarding a composition that is well-defined and a preparation that meets Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). This process is expensive, so substantial funds must be available in order to finance these trials.

Thus, a significant proportion of the clinical studies that have been conducted with cannabinoids (particularly with THC and CBD) used Nabiximols/Sativex, and more recently Epidiolex. The importance of the studies carried out with these two drugs is undeniable, as well as the legitimacy of any pharmaceutical company (in this case GW Pharmaceuticals) to defend their interests and obtain the maximum financial gain from their investments. However, it must be emphasised that this situation is actually a bottleneck for other studies to be conducted and it does not help to broaden our knowledge of the therapeutic activity of cannabinoids, nor does it help patients who could benefit from the use of other cannabinoid drugs with the same active substances but in other proportions or presentations.

Therefore, I believe that it is vital to advance the development of additional clinical trials with drugs that have THC and CBD, using a formula that is not restricted by the interests of a given pharmaceutical company. The question is, who can actually develop these studies? And, no less importantly, who is willing to do so? Can the necessary investment be covered? There is no single answer to these questions, though, as we shall now discuss, it would be desirable for a significant part of the weight of such clinical trials to fall on the cannabis industry.

Situation of the cannabis industry related to the therapeutic applications of cannabis extracts

Ever since several countries approved the medicinal, and even recreational, use of cannabis, there has been a significant increase in the number of companies that produce cannabis and its derived products. The investments in and growth of this sector have been noteworthy over the past few years, and a significant amount of capital has accumulated in these companies.

However, given the highly different regulatory environments in different countries, the possibilities to market products are still limited in many cases. In countries or states where the recreational use of cannabis is approved, a clear line of business is based on offering products to the consumer of recreational cannabis. On the other hand, in countries where medicinal cannabis programmes have been approved, the option exists to provide products with a therapeutic purpose and that logically must meet requirements that are different regarding safety (more similar to those of a medication), as well as the amounts of active substances present in these preparations, whose precise doses must be known.

As mentioned above, the evidence that has been built up to now indicates that the therapeutic effect of these extracts is mostly due to the content of THC and CBD. Remember that the natural cannabinoids taken from the plant are limited by the fact that they cannot be patented. This is why part of the industry has chosen to search among different cannabis extracts for the presence of certain components, including minor cannabinoids and terpenes with therapeutic activity. This approach is based on the idea that the presence of other minor cannabinoids, as well as different terpenes, could produce the so-called entourage effect. At present, little scientific evidence justifies the existence of this entourage effect, and much less that it makes an extract selective enough to treat one disorder or another. However, it is frequent for different cannabis extracts or preparations to be attributed therapeutic properties that specifically treat one illness or another, based on the presence of any such minor components. If this approach is followed, each company would have to find its own formula or formulas combining different components. This is undeniably an interesting strategy in the long term, though it can be difficult to find that combination and, above all, to identify its many possible pharmacological targets and to prove that the therapeutic action of such extracts is not solely due to the presence of THC and CBD. This is why I believe that the entourage effect is mostly a marketing strategy until more is known about it. This may be understandable when such preparations are used for recreational purposes, but not (at least based on what we currently know) for therapeutic use, which naturally must be supported by scientific evidence. At any rate, the question is whether it would be possible to develop in parallel a strategy that would allow the cannabis industry to be able to assign at least part of its resources to the development of collaborative clinical trials.

A possible solution: collaborative clinical trials with cannabinoids

Considering all that has already been discussed in this paper, it may be difficult for a pharmaceutical company with ties to the cannabis industry to undertake the development of clinical trials if it is not done with a drug or preparation whose intellectual property is protected. How to get around this obstacle? One possibility to be able to advance in the development of clinical trials, and thus obtain results that may turn into a benefit for patients as quickly as possible, is for the responsibility of these trials to not fall on a single company. This option has already been explored at other times for different disorders and would be based on the establishment of one or several international consortiums. These consortiums could be made up by several pharmaceutical companies, or companies with interest in the medicinal cannabis sector, which together would provide the necessary resources to be able to conduct clinical trials that would analyse the therapeutic potential of cannabinoids and, more importantly, that of THC, CBD, and their combinations. There may be many formulas to establish this type of consortium in which the degree of participation of each company would have to be determined, but its basis could be that none of them would individually carry the expenses and risks from undertaking such clinical trials. Ideally, these initiatives could also receive donations from foundations or non-profit organisations (many of which are already collecting funds for this purpose) or even public bodies interested in promoting the development of clinical research with cannabinoids. The greatest benefit of this type of approach is that it would ideally have enough resources to conduct clinical trials that would otherwise be challenging to carry out. Development of these trials would lead to the fast and transparent reinforcement of the scientific evidence sustaining the possible use of cannabinoids for different therapeutic applications. It would obviously be essential to establish the characteristics of the cannabinoid drugs that would be used in these trials in order to make them easy to standardise. When results are positive, it would be ideal for this approach to enable regulatory agencies to approve certain generic cannabinoid medications or preparations for particular applications. This way, accredited companies would be able to manufacture, distribute, and sell such generic products, which could be prescribed and used in a greater number of applications once they have been approved.

This approach is unmistakeably heterodox from an entrepreneurial point of view. However, I believe that it could decisively contribute to expedite clinical research with cannabinoids, something that today is necessary to improve the circumstances of millions of patients who could benefit from the therapeutic properties of cannabinoids and whose situation cannot wait.