By Manuel Guzmán

Manuel Guzmán is Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Complutense University of Madrid, member of the Spanish Royal Academy of Pharmacy, and member of the Board of Directors of the International Association for Cannabinoid Medicines. His research focuses on the study of the mechanism of action and therapeutic properties of cannabinoids, especially in the nervous system. This work has given rise to more than one hundred publications in specialized international journals, as well as to several international patents on the possible therapeutic applications of cannabinoids as anticancer and neuroprotective drugs. He routinely collaborates with scientific reviewing and funding agencies.

The recent decision of the Canadian Senate to open the doors to regulating the recreational use of cannabis constitutes a historic event for a sovereign State that belongs to the G7. Since 2001, this country had already implemented through its "Health Canada", its Ministry of Health, one of the first and most ambitious medical cannabis dispensing programmes at international level.

This programme was followed by others (for example, in the Netherlands, Israel, Germany and Uruguay) and one year later, by various countries around the world (for example, Switzerland, Greece, Luxembourg, Portugal and the United Kingdom, just to mention some in Western Europe) they have moved towards the path of approval for the therapeutic use of cannabis and its by-products. All this brings the lively debate back to the public opinion and the media about the clinical use of the preparations of the plant. And, in our closest environment, the ever-present question is reopened of: "When will there be medicinal cannabis in Spain?"

Although cannabis has been used medicinally for at least five millennia, the precise aspects of how its active components (the so-called "cannabinoids") act on our organism were not clarified until the 1990s. From then on, scientific research on these compounds have experienced a spectacular boom, thanks to which today we know quite reliably how cannabinoids act in the body and what may be some of their most immediate therapeutic applications. However, the legal restrictions that exist for decades to investigate, prescribe and dispense cannabis by-products have greatly hindered the study of the therapeutic potential of this plant, so that there are currently few works that thoroughly meet the methodological criteria necessary for considering them as controlled clinical trials. In spite of this, some of these clinical trials, together with numerous observational studies, have contributed their bit to this field and generally speaking they support the use of these substances quite consistently in the treatment of symptoms associated with various diseases.

What do we know today about the therapeutic potential of cannabis? In the first place, like any drug we must weigh up its therapeutically relevant effects with respect to their undesired side-effects. With regard to the latter, clinical studies carried out with cannabis preparations and purified cannabinoids reveal that their safety profile is more than reasonable and that the side-effects such as drowsiness, disorientation, confusion and hypotension sustained by some patients usually fall within the accepted margins for other medications. Despite this, the clinical use of cannabis and its by-products is still limited.

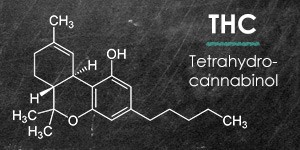

The therapeutic effect that was first formally established for cannabis and purified cannabinoid preparations was the inhibition of nausea and vomiting in cancer patients treated with chemotherapeutic agents. Thus, the prescription for this indication of Marinol capsules (medicine composed of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, the most potent cannabinoid in the plant) and Cesamet (medicine composed of nabilone, a synthetic derivative of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol) has been allowed in the USA and other countries for a long time), as well as the dispensing of standardized samples of medicinal cannabis. Among other clinical uses of cannabis, we can highlight the treatment of chronic pain cases due to a very diverse etiology (neuropathies, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, oncological pain, etc.). In fact, Sativex, an oromucosal spray composed of a mixture of two cannabis extracts, one rich in Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and another rich in cannabidiol, is approved in Canada for relieving pain associated with multiple sclerosis and cancer. Furthermore, cannabinoids have shown therapeutic use in the spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis (Sativex can be prescribed in many countries for this indication), as well as in cachexia or wasting syndrome (massive weight loss) that occurs in cancer or AIDS patients.

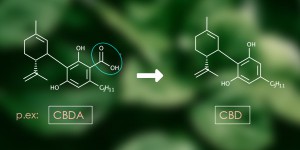

There are other therapeutic possibilities for cannabinoids that are still in the earliest stages of clinical studies, although they are not necessarily less important. They include one that in recent years has had greater repercussion not only at clinical but also mediatic level and that is the use of cannabidiol for relieving seizures in refractory paediatric epilepsies. In fact, Epidiolex, a drug that contains cannabidiol as an active ingredient, has just been approved in the USA for that purpose.

Is cannabis, as some claim, the "aspirin of the 21st century", that is, a panacea and remedy for healing innumerable ailments? Or on the contrary, is it, as others claim, a plant with no medical use and which is even cursed, that makes people "go crazy" and opens the door to consuming hard drugs? Obviously, neither of the two assertions seems plausible. The fact that in almost every corner of our body there are specific molecules that recognize cannabinoids and mediate their actions makes the therapeutic potential (at least theoretical) of these compounds extensive, especially in the case of "orphan" diseases, for those for which there are still no effective therapies.

However, in some other conditions, for which well-established drugs are already available, the effects of cannabinoids tend to be relatively moderate. However, it is worth noting that cannabinoids combine some very different actions that, although each might be mild in intensity, together they allow different diseases to be fought simultaneously and, therefore, "kill several birds with one stone". A clear example of this is the palliative treatment of cancer patients, in which cannabis and its by-products can, for example, inhibit nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy, reduce loss of appetite, relieve pain, reduce anxiety and fight insomnia.

Despite the fact that, at least on paper, medicines containing purified cannabinoids have a more standardized pharmacological profile than the crude preparations of the cannabis plant, the latter (in the form of oils, for oral administration, or flowers, for vaporized administration) are almost always better tolerated by the sick. This is perhaps due to the fact that there are compounds in the plant, such as the aforementioned cannabidiol and perhaps other cannabinoids and some terpenes, which can enhance some therapeutic effects and relieve some side-effects of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Clearly, different medications in general and different cannabinoid preparations in particular may have greater or lesser clinical benefit in different patients. Therefore, we should never forget that each patient is a unique human being and as such deserves to be treated.

In the current Spanish scenario, therapeutic cannabis users usually find themselves in great legal and health insecurity due to the lack of a regulatory system that allows safe access to standardized preparations of the plant. This fact entails an important lack of information received by patients and their carers, as well as in the training of health personnel (doctors, nurses, psychologists and other specialists) regarding the medicinal use of cannabis.

In short, the new winds that seem to blow in the world, specified in the already implemented regulations on medicinal cannabis - or in the process of being implemented - in many countries, clearly show the need for Spanish government administrations to review the obsolete legal restrictions that still prevent many doctors and patients from freely and openly deciding on a practice that, on the other hand, is increasingly common in our environment.